Feature Articles

December 2023 AAALetter

Table of Contents

- No Sked, Chance em! | Lee A. Tonouchi

- Integrating JEDI in Graduate Student Work: For Beginners | Jazmine Exford

- A Transformation from Africa | Olumide Ajayi, Bukunmi Ogunsola, and Pamela Kimario

No Sked, Chance em!

Lee A. Tonouchi, Independent

AAAL 2023 Distinguished Public Service Award Recipient

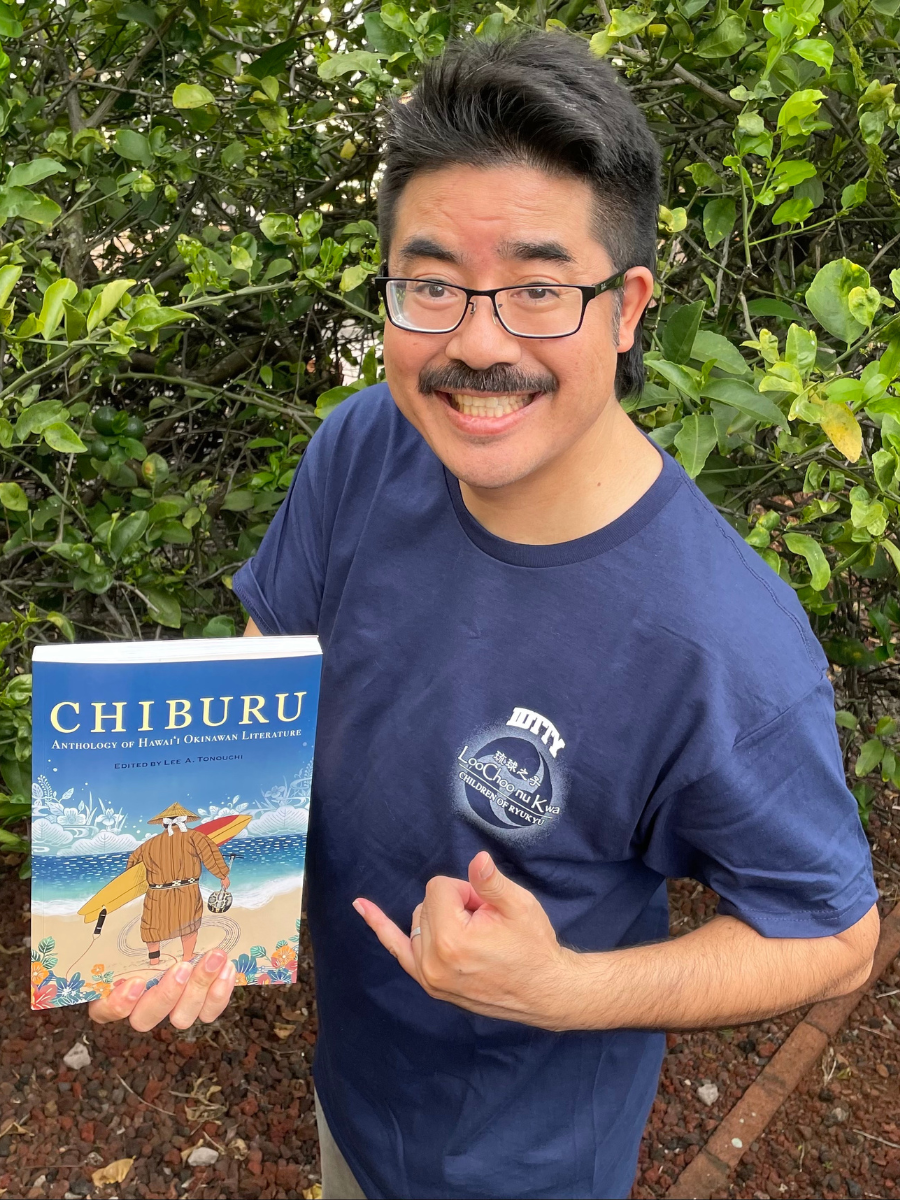

Lee A. Tonouchi with his latest book, Chiburu: Anthology of Hawai‘i Okinawan Literature

My Maui Gramma grew up working da sugar cane plantation fields in Lahaina. She wen work her way up fo be one of only two women irrigators on top da whole island. Usually only men wen get dat position, but she wen go confront da plantation boss and convince him dat she could do da job. My Maui Gramma wen work hard her whole life, and she had so much fo be proud of, but yet she had one secret shame. Whenevah she talked, she always wanted me fo “correck” her. She said she only went school up to eight grade, so she felt she no could talk English so good. As why when she wen move O‘ahu, whenevah we went out someplace, she wanted me fo talk fo her cuz she nevah like people hear her Pidgin.In school I wuz condition fo feel da same way. Teachers always used to tell, “Lee, you write like how you talk.” I thought dey wuz giving me one compliment, but dey said, “No, that's bad.” But to me, dat wuz da language dat wuz real, cuz those wuz da kine words I wuz surrounded by. But in order fo get one good grade in school, I wen try my bes fo listen to da teacher.

Wuzn't till I went da University of Hawai‘i dat I had one epiphany. I wuz fortunate fo take one literature survey class wea da Professor, Rob Wilson, wuz using one Hawai‘i literature anthology called The Best of Bamboo Ridge as one of his textbooks, alongside traditional stuff like Shakespeare and Faulkner. And dis wuz at one time when not too many professors considered Hawai‘i’s Local literature fo even be worth studying. Most my friends went their whole college careers nevah encountering no Local literature whatsoevahs. So I wuz lucky I had one cool professor, cuz inside dat collection had one Pidgin poem dat wen change my life. Da poem we wen study wuz “Tutu on da Curb” by Eric Chock. Wuz my first time seeing Pidgin in literature.

In Hawai‘i, da Pidgin talker stay perceive as being less intelligent than da standard English talker, so da way I saw ‘em wuz as means you get two choice den. You can either change yourself, or you can try change da perception. To me no wuz right dat people had fo be shame like my Maui Grandma. So in dat moment I wen go decide fo dedicate my life to trying fo change da perception. As how I became known as “Da Pidgin Guerrilla.”

I tink so I got dis award cuz I no wuz afraid fo take one stand and say das wrong brah, fo be prejudice against Pidgin talkers. Mostly all Local writers who use Pidgin believe get times when you should use Pidgin and get times when you no should use Pidgin. Pretty much I da only person I know who said should be up to da person. As why I wen decide fo use Pidgin ALL da time and WRITE EVERYTING in Pidgin. Fo da record, I can write and talk English, but as my choice not to. Growing up, people always used to tell you no can do dis, and you no can do dat with Pidgin. But I wen figgah, nobody wen even try befo so how dey know no can? I knew no wuz going be easy and I would probably get lotta flak. But I said, ah, no sked, chance em.

I wen encounter some no so nice people ova da years, but I got some national awards and recognitions along da way too. My Pidgin poetry collection won da Association for Asian American Studies Book Award. My Pidgin children’s picture book won one Skipping Stones Honor Award. My Pidgin play wuz one Los Angeles Times Critic’s Choice Selection. My Pidgin essay wuz inside da academic journal College English. I wuz even one Pidgin witness wea I wen submit my expert written court testimony in Pidgin, and we won da trademark case! So I would like fo tink da question no longer stay if can or no can. I hope I wen prove dat just like any oddah language, you can do everyting with Pidgin.

Fo get dis Distinguished Public Service Award from da AAAL means a lot to me, cuz dis kine prestigious national validation helps da cause. It makes da discriminators question what dey tink dey know about Pidgin.

My Maui Gramma stay pass away, but I tink she would be most proud of dis award. Cuz she wen help make me who I am, so I feel like we won dis award togeddahs, and dis award stay not only fo us, but fo all da Pidgin peoples, li’dat, you know da kine.

Integrating JEDI in Graduate Student Work: For Beginners

Dr. Jazmine Exford

Jazmine Exford, Florida International University

AAAL 2023 Distinguished Service and Engaged Research Graduate Student Award Recipient

Applied linguists and members of AAAL are no strangers to advocating for scholarship with real-world impact. Moreover, both groups continue to take steps to recognize the value of scholarly efforts that specifically center principles of justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (JEDI); for example, see President Lourdes Ortega’s statement in the June 2023 issue of the AAALetter. These steps demonstrate that we are beyond acknowledging that JEDI work must be done and are now implementing more strategies to financially support this work and recognize it as meritorious scholarly productivity. As a proud 2023 recipient of the new Distinguished Service and Engaged Research Graduate Student Award (DSERG), I was asked to share about the impact of my work and to provide some words of wisdom to graduate students who find similarities in our trajectories.

As a graduate student, I was dedicated to JEDI-informed projects in which I could use my scholarly expertise to support the inclusion of Black communities in sectors of higher education where we remain underrepresented, namely linguistics, world language education, and international education. As one example, I served as an expert committee member on an initiative between two minority-serving institutions in Florida that created a Spanish-language curriculum centered on Blackness. Specifically, it celebrates the linguistic and cultural practices of AfroHispanic populations, includes ways to discuss Black experiences (e.g., hair textures/styles, etc.), and shares videos of Black Spanish learners describing how they use Spanish in their local and international communities. This opportunity allowed me to blend my personal, professional, and academic experience to create solutions to address the lack of planning for Black students in world language education.

As an assistant professor, my projects expand on the JEDI outcomes of some topics I explored in graduate school. My dissertation examined the acquisition experiences of Spanish learners of color, including how their racio-gendered embodiment informed the sociolinguistic variation they encountered and the benefits of using autoethnography as a method to agentively learn and navigate sociolinguistic variation. This project and my current ones expand contemporary discussions on how to address sociolinguistic variation in second language courses. These are contentious debates, since linguistic variation is not evaluated socially in neutral ways, making the inclusion/exclusion of language variation in the curriculum a political issue that must be informed by JEDI. Within my larger research trajectory, my work will continue using sociocultural linguistics to inform world language education to better address the needs of students of color and to embrace racio-gender identity, intercultural community dynamics, and social interaction as political discourse. Below, I close with some thoughts about integrating JEDI principles in graduate work.

Examine your community roles and the people you serve in those roles

When starting JEDI work, my first sites of inquiry are my community roles and the needs or interests of the people I serve in those roles. While I was ABD (all but dissertation), I was an English instructor in a small town in Mexico. I examined the challenges that my students and I faced interacting with a curriculum that excluded linguistic and cultural diversity and functional approaches to using English outside of standardized tests. I subsequently received a grant from my graduate university to redesign the curriculum to begin addressing these issues. So I ask: What challenges have you faced in your personal or professional roles? What challenges are faced by the people you serve in those roles? How do JEDI outcomes mitigate those challenges?

Identify specific JEDI issues that your personal and academic expertise can address

Although I value the implementation of JEDI principles across various sectors, I acknowledge not having the personal ability to address all JEDI-related issues. JEDI work is a collective effort that requires many actors’ insights, skill sets, and resources—some of which my experience and access had not yet afforded me. While there are countless ways that JEDI can be implemented in applied linguistics, I have focused on identifying the specific JEDI-related issues that my personal and academic expertise were uniquely set up to address, which for me, are issues of language and identity in Spanish-language curricula. What might be some of yours?

Remember that examining minoritized populations is not inherently JEDI work

Although I study the acquisition experiences of Spanish learners of color, this topic isn’t inherently rooted in JEDI principles simply because it’s underexplored or centers on race. Those connections need to be drawn explicitly. For me, I problematize how the multilingual experiences of communities of color are institutionally devalued, which directly informs the lack of planning and recruitment of Black students for world language education. Through these connections, my research topic can help support JEDI outcomes, such as designing curricula that increase Black students’ access to multilingual education and educators’ capacities to serve these learners. How does your work on minoritized topics, experiences, or communities, directly inform JEDI outcomes?

Align your JEDI efforts with your graduate milestones

Because doing JEDI work meaningfully takes considerable intention, I used my graduate milestones (e.g., thesis and dissertation) as opportunities to integrate these principles into my work. For instance, my dissertation project started as a JEDI-rooted service opportunity, and what I learned from that experience inspired a chapter of my dissertation. This is an alternative approach to viewing JEDI work as a set of miscellaneous tasks (e.g., workshops, modules, certificates, etc.) that are separate from research topics or processes. What are your academic milestones, and how can you use one or more of them as an opportunity to specifically integrate JEDI principles and outcomes?

In all, I am excited about the direction of the field and its reception of the emergent scholarship of graduate students who are taking JEDI work to new levels. I remain inspired by many applied linguists whose JEDI-informed work provided me the language I needed as a graduate student to find the trajectory I’m on today. I hope I will eventually do the same for upcoming students, starting with these aforementioned suggestions. To all who are reading: let’s remember to preserve ourselves in an industry that far too often asks, “What have you done for me lately?” With all this precarity, I hope you continue to find purpose and liberation in your work. And I hope you continue to do so with your health and spirit intact.

A Transformation from Africa

Olumide Ajayi, Bukunmi Ogunsola, and Pamela Kimario, University of Georgia

We appreciate this exciting opportunity to contribute a piece to the AAALetter. Since we began attending the AAAL conference in Pittsburg in 2022, AAAL has served as a professional home, and we are deeply honored by the relationship we have nurtured, especially this opportunity to lend a voice to the critical role of African scholarship in applied linguistics research. In telling the rich and unique stories of transformation that resonate in the collective experiences of emerging African scholars doing amazing work within applied linguistics, we conceived this piece as an exposé regarding the insights nested in thinking with knowledge and resources sourced from Afrocentric scholarship.

Applied linguistics, like many fields in the humanities and social sciences, has formed different agendas and shaped and experienced various turns (May, 2014). Some turns have arisen and fallen along with the changing socioeconomic and political leanings of scholars in the field. Yet other turns have been in response to intrinsic incongruencies in the discipline or adjacent fields, cross/interdisciplinary advances, and/or epistemic and ontological shifts (Makoni & Pennycook, 2012; Maldonado-Torres, 2007). This article is not about defining or responding to a broader call about normalizing multi-(ies): multilingualism, multimodality, multiliteracies, multiculturalism, multilingual practices. Rather, we seek to create awareness, to locate the ways of being, knowing, and doing of emerging African scholars—particularly, graduate students—who are learning the ropes of scholarship in applied linguistics in the Global North and deciphering points of convergence, divergence, and departure. In a sense, it’s about sleepwalking next to a pot of broth.

As emerging scholars carving a niche within this field, we are surrounded by the crossfire of “gestures of exclusion” (Connell, 2007) on one hand and “rhetorics of inclusion” (Furo, 2018) on the other. The former is fronted through mandatory immersion in systems, institutional structures, methodologies, and community of practice that rarely center Afrocentric onto-epistemologies (Juffermans & Abdelhay, 2017; Wandera, 2020), while the latter thrives on sprinkling doses of belongingness through such moves as encouraging and embedding a Global South agenda or drawing on indigenous knowledges without necessarily honoring local ways of thinking or acknowledging non-Western procedures of knowledge production (Kubota, 2020). Of course, Africa, the world’s most linguistically diverse continent, possesses an extraordinary wealth of knowledge that the fields of language education, literary studies, and socio- and applied linguistics can draw from and think with. Yet the potency remains peripheral, annexed, and disregarded. To this end, we recommend the following three ways to depolarize and re-imagine support for emerging scholars of African descent doing applied linguistics work.

Reflecting on epistemic variance

Epistemic choices are crucial decisions researchers undertake to resolve real-world issues. In an effort to uphold methodological “rigor” in scientific research and to adhere to prescribed guidelines, local epistemic systems are frequently isolated or disregarded, leading to imbalances (Owusu-Ansah & Mji, 2013). Many scholars of African descent consider local epistemic choices (such as oral traditions, stories, legends, riddles, songs, proverbs, folk tales, poetry, dance, and music) as tools to foreground local context worldviews. Leveraging their philosophies and thought processes can prevent the silencing of crucial epistemic voices.

Recruitment of African-background scholars in applied linguistics

A quick online search for African scholars holding faculty or tenure-track positions in applied linguistics departments reveals a relatively small presence. Due to the perception of limited career opportunities, potential candidates routinely settle for other well-funded programs, such as comparative literature, cultural studies, or African studies. Some of these scholars possess a strong background in linguistics and could make significant contributions to applied linguistics research. Thus, we believe that the active recruitment of African-background scholars will serve to demonstrate the commitment of applied linguistics to Afrocentric epistemologies.

Increased collaboration with Africa and African diaspora communities

Implementing conscious bias training and broadening the diversity of reviewers and editorial boards to include scholars of African descent can foster increased collaboration with Africa and African diaspora communities. A recent New York Times article (Walsh, 2023) asserted that the world is increasingly becoming more African due to a thriving youthful population, positioning several African countries among the world's leading economies in the next two decades. This significant shift is currently underway, as the number of African immigrants to the United States continues climbing (Bah & Kagotho, 2023; Chenane & Hammond, 2022). Research also shows that, among the immigrant population in the United States, Africans are among the most highly educated (Kumi-Yeboah, 2016; Kumi-Yeboah & Smith, 2017). Consequently, it is essential for the field of applied linguistics to be well prepared to engage in meaningful collaborations and to promote the publication of African scholarly work.

In conclusion, as we continue to engage with and (re)negotiate turn after turn, it is our hope that the next turn will break the dominant cycle and give birth to new gazes, because, according to Harklau (2022), “what we call something, how we talk about it, can actually shape our sense of objective realities and therefore how we act upon the world” (p. 234). We envision a more integrative and depolarized view of language, literacy, and educational research.

References

Bah, F., & Kagotho, N. (2023). “If I don’t do it, no one else will”: Narratives on the well-being of Sub-Saharan African immigrant daughters. Affilia, 08861099231183667.

Chenane, J. L., & Hammond, Q. (2022). Using social media to recruit participants for scholarly research: Lessons from African female immigrants in the United States. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 33(4), 509–525.

Connell, R. (2007). Southern theory: The global dynamics of knowledge in social science. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

Furo, A. (2018). Decolonizing the classroom curriculum: Indigenous knowledges, colonialism, logics and ethical spaces. Ottawa: University of Ottawa.

Harklau, L. (2022). Adolescent second language learning and multilingualism. Oxford University Press.

Juffermans, K., & Abdelhay, A. (2017). Literacy and multilingualism in Africa. In B.V. Street & S. May (Eds.), Literacies and language education (3rd ed., pp. 353–365). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Kubota, R. (2020). Confronting epistemological racism, decolonizing scholarly knowledge: Race and gender in applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics, 41(5), 712–732.

Kumi-Yeboah, A. (2016). Educational resilience and academic achievement of immigrant students from Ghana in an urban school environment. Urban Education, 55(5), 753–782. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085916660347.

Kumi-Yeboah, A., & Smith, P. (2017). Cross-cultural educational experiences and academic achievement of Ghanaian immigrant youth in urban public schools. Education and Urban Society, 49(4), 434455. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124516643764.

Makoni, S., & Pennycook, A. (2012). Disinventing multilingualism: From monolingual multilingualism to multilingual francas. In M. Martin-Jones & A. Blackledge (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Multilingualism (pp. 439–453). Abingdon: Routledge.

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2007). On the coloniality of being: Contributions to the development of a concept. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 240–270.

May, S. (ed.). (2014). The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL and bilingual education. Abingdon: Routledge.

Owusu-Ansah, F. E., & Mji, G. (2013). African indigenous knowledge and research. African Journal of Disability, 2(1), article 30. https ://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v2i1.30.

Walsh, D. (2023, October 28). The world is becoming more African. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/10/28/world/africa/africa-youth-population.html.

Wandera, D. B. (2020). Resisting epistemic blackout: Illustrating Afrocentric methodology in a Kenyan classroom. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(4), 643–662.